Technology historian Bill Burns

talks about trans-ocean communication

How would you communicate differently if you knew your message would take days, weeks, or months to arrive? Would

you bother less often or put more thought into what it said? Maybe there would be little difference other than the

inconvenience of time delay. I was wondering that when an episode of PBS’s ‘History Detectives’ came on and

featured a segment about transatlantic cables. Afterward, I did some research out of curiosity and came across a

very informative website on the topic. It’s published by Bill Burns, a technology historian, and I later found out

that he actually assisted with that History Detectives segment. In the hope that other people might be as interested

as I was, I asked to do this interview article and he was more than helpful.

Q. When you consider the usefulness of the telegraph system for that time, it seems inevitable that it would

expand to the other continents. Is that mostly how it was viewed in the mid-1800s or were there a lot of skeptics?

A. The first cable was laid between Dover and Calais in 1850, and failed almost immediately; the technical and

commercial success of a second cable on the same route a year later began a boom in undersea cables, with many

companies promoting them. By 1854, when Cyrus Field proposed to lay an Atlantic cable, a number of other short

lines were in operation between mainland Britain and Ireland, and Britain and Europe. They were making good money

for their owners, but there was certainly considerable skepticism that a 1600-mile line from Ireland to

Newfoundland would work.

However, this was the Victorian era of technological enthusiasm where everything seemed possible, and investors

ponied up cash for several failed attempts at the Atlantic cable before its eventual success. The amounts

invested will give an idea of the potential of the cable - each attempt cost in the region of a million dollars at

the time, the equivalent of about $100 million today.

Q. Was it a bigger challenge to make a cable that long or to lay it across the Atlantic seabed?

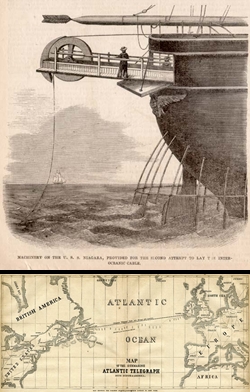

A. In 1857, when the cable was made for the first attempt at the Atlantic route, manufacture of submarine cable was

a routine operation. Because of the length required the work was split between two factories, but there was no

great difficulty in making such an amount of cable. Laying it was the challenge. A single ship could not carry the

sheer weight and volume of the cable, and it was even a borderline overload when split between the British ship HMS

Agamemnon and the American ship USS Niagara. And the depths of the Atlantic, up to 12,000 feet, were far greater

than for any prior cable.

Q. They must have coordinated a day, time, and message to test the first cable after it was laid. At the time

though, the only form of transatlantic communication was through letter carried by ship. What was it like to set

up that first testing procedure?

A. Surprisingly, it was very simple. Every cable ever laid since 1851, including the large number of fiber optic

cables now in use, was continually tested during the laying operation. The standard procedure in laying a cable

is to start at one end with the connection to the land-based equipment, then steam ahead to the destination,

paying out the cable. Transmitting and receiving equipment on the ship is connected to the shipboard end of the

cable, and signals are exchanged with the shore at regular intervals.

Because of the use of two ships for the 1858 Atlantic cable, this procedure had a slight variation; the ships met

in mid-ocean, spliced their cables together, then set off in opposite directions for Ireland and Newfoundland.

Communication was maintained between the two vessels through the cable at all times. Once the cable was landed at

each end, the shore stations took over the job of signaling.

U.S.S. Niagara laying cable

1858 Atlantic cable route

Courtesy: Atlantic-Cable.com

Q. The cable had severe attenuation problems and really couldn't deliver a useful signal. What was the main reason

for that?

A. Rigorous theories of signal transmission through underwater cables had not been developed at that time, and

there was considerable disagreement on the best way of designing and working a long line such as the Atlantic

cable. Unfortunately, a number of bad choices were made, such as the small size of the copper conductor, and

working the cable with a very high voltage (up to 2000 volts from a large induction coil). There were also

limitations in the quality of the materials used, particularly the copper, which was of low purity. This was not

critical on short cables, which could be worked more or less like landlines (although even these could be used

only at a slow rate of signaling), but for the long cable they proved fatal.

Q. As I understand it, that cable could not be salvaged and they had to install a new one with significant

design improvements. Once they had a working system, what was the bandwidth and how was it allocated to its

users?

A. After the failure of the 1858 cable there was a seven-year delay before another attempt was made. In the

meantime there had been a long and thorough British Government inquiry in 1861 on the problems of making,

laying, and working long cables, and the outcome of this was a clear view of the causes of the failure. Following

this, based on mathematical calculations of the electrical behavior of long cables, William Thomson (later Lord

Kelvin) developed much improved transmitting and receiving instruments, which allowed the cable to be worked

using a low voltage (no more than 100 volts).

These advances led to a much-improved design of both the cable and the equipment for the 1865 cable expedition.

While this cable broke during laying and could not be recovered, a second cable to the same design was laid in

1866, and the end of the 1865 cable was then retrieved and the run completed.

The bandwidth of these first Atlantic cables was just a few words per minute, and they carried only one signal

at a time in one direction only - the cable was switched at each end between transmit and receive modes as

needed. The cables were worked by hand, with the operator at the transmitting end using a special "cable key" to

send Morse code - not as dots and dashes, but as positive and negative voltage pulses. The operator at the

receiving end would watch the signal on a very sensitive "mirror galvanometer", which indicated the dot and dash

signals by a small deflection to the left or right.

Early William Thomson mirror galvanometer, used on board USS Niagara in 1858

(Science Museum, London)

Courtesy: Atlantic-Cable.com

Q. How would you compare the telegraph with the Internet in terms of being a revolutionary technology?

A. In a way, the early cables were more revolutionary, as they reduced the round-trip message time from days and

weeks (or even months in the case of Australia) to just a few minutes. This was a major and disruptive change at

the time, and revolutionized government, war, and commerce - but not personal communication. Private individuals

would seldom send a "cable" because of the very high cost, which persisted until the end of the 19th century.

By contrast, the Internet can be viewed more as a gradual outgrowth of existing technology, starting in the early

1970s by connecting just a few university-based computers over dial-up telephone connections for program and data

sharing, followed by the use of this network for email and ‘Usenet’ newsgroups. This was not really any great

advance over the existing worldwide communications technologies of the telephone and fax machine. Even in the

1980s, the availability of public dial-up networks and the rise of the personal computer were relevant to only a

very small percentage of the population. It wasn't until the beginnings of the World Wide Web in the 1990s that

there was any perception of the Internet among the general public.

Q. Now, virtually all submarine cables are high-bandwidth fiber optic. What would you anticipate would be the

next major leap in global communications technology?

A. As Arthur C. Clarke famously noted, it's unwise to try and predict what will or will not happen in new

technology, but I don't think there will be another leap for quite some time. The transition from copper

cables to fiber optics beginning in 1988 (the year the first Atlantic fiber-optic cable was laid) was the last

major innovation - all developments since then have been solely to increase bandwidth. Geostationary satellites,

while essential for getting signals to remote areas not served by cables, are an evolutionary dead end, as their

bandwidth is limited and the round-trip signal time far too long. Low earth orbit satellites now proposed would

mitigate these problems, but again would be useful mostly for remote locations, as fiber optic connections are

cheaper and more reliable. I expect that most progress will be in the form of extending fiber optic connections

to every endpoint, giving users virtually unlimited bandwidth - but no doubt for a price.

Q. In your work as a technology historian does it seem to you that technology evolves faster or slower than

most people perceive?

A. Until perhaps the 1930s, individual inventors were largely responsible for technological advances, and their

work was often well publicized - think of Morse, Edison, the Wright brothers in America; Faraday, Thomson,

Marconi, Fleming in Britain; and a host of still-familiar names in other countries. Their technology was also

at least somewhat comprehensible to most people, and I don't think it was too difficult for an educated person

to have a good general idea of advances in most fields.

The situation is much different today, with vast teams of scientists and engineers having largely replaced

individual inventors. Even as an electronics engineer I can keep up with only a very small part of my own field,

and with just a tiny fraction of science and technology developments in general. I suspect that most people

have very little idea of where technology is going and how fast, seeing only the commercialized offshoots such

as electric cars, big-screen televisions, and smart phones. Sadly, this disconnect seems to have led to a lack

of understanding and appreciation of science and technology, and for many people overt hostility.

Q. Which technologies do you think are the most overrated, and which ones would you consider underrated?

A. This has no easy answer, as it's impossible to predict what will be useful in the future. I believe that

basic research in every field, no matter how unimportant it may seem to politicians, is the most important key

to future prosperity.

Q. As a historian, you're always looking for things to enhance and add to your collection. Are there certain

specifics that interest you the most?

A. The official record of historical events, whether from newspaper reports or contemporary books, is only

part of the story. What I've found most useful and interesting in researching cable history are the accounts

of individuals who worked in the field from the 1850s until the present day. These may take the form of

diaries, letters, and oral histories, together with photographs and drawings, and they give a much more immediate

and personal connection to the events described. For example, the mechanical engineer responsible for the cable

machinery on all the early Atlantic cable expeditions was a man named Henry Clifford. He was also an accomplished

artist, and I have a painting by him of the Great Eastern on the 1865 cable expedition, along with his family

history and copies of photographs. I've also met his great granddaughter, who shared stories and documents that

came down in the family. This kind of connection with the events of 150 years ago is priceless.

Q. Do you think our society appreciates historical perspective and knowledge of the past as much as it should?

A. Yes, and no. Television programs such as History Detectives on PBS in the USA, and historical documentaries

by both the BBC and PBS, are well received - but only by a rather limited audience. And many museums are

struggling for funding in the present economic downturn, where they seem to be an easy target.

Bill Burns' web site: http://www.atlantic-cable.com/